Home Truths

First published in the TasWeekend magazine (The Hobart Mercury)

A child strolls along a Tasmanian beach with his parents and wonders why the tide is further out than it was at the same time the day before. He asks the question out loud, and before long that single query has shaped the entire next term of his education. That’s because this child comes from one of the 1036 Tasmanian families who have decided to ditch school and instead teach their kids at home. Some call it natural learning. Others call it unschooling. Whatever the description, this isn’t learning as you know it.

The woman in charge of these home education programs is Katherine O’Donnell. She estimates around 70 per cent of the state’s home educators follow an eclectic program borrowing from all different types of teaching and learning styles to adapt to suit what their children are most interested in. About 100 of the parents are qualified teachers.

"The really, really clever, engaged and amazing home educators can take a situation like this child on the beach questioning the tides and spring-board a whole work pattern of everything covering geography, science, writing stories and reading books about the ocean, measuring the length of the tide from day-to-day and working out averages,” O’Donnell says. “It’s a really amazing thing to see.”

Home education requires parents to have patience, she says, something this ex-lawyer admits she doesn’t have enough of. Her two children both attend school. A few years ago her family went on a holiday to Europe for four months and O’Donnell tried to teach the children through an e-schooling program. “And they told me in no uncertain terms that I’m never to home educate them because apparently I’m really bad it it,” she says. Her mistake: her approach was far too structured. “I would sit down and say ‘okay we are going to do maths from 10 to 11 and then we are going to do history from 11 to 12’ and completely block it all out and the kids would be bored senseless and I’d go mad,” she says. “It’s something we often see - parents who start off thinking that a structured approach is what they are going to do then after about three weeks completely turn it upside down and realise they are never going to stay sane doing that. That happens a lot. People realise they need to relax into it and really follow their children’s lead and find the things they are interested in.”

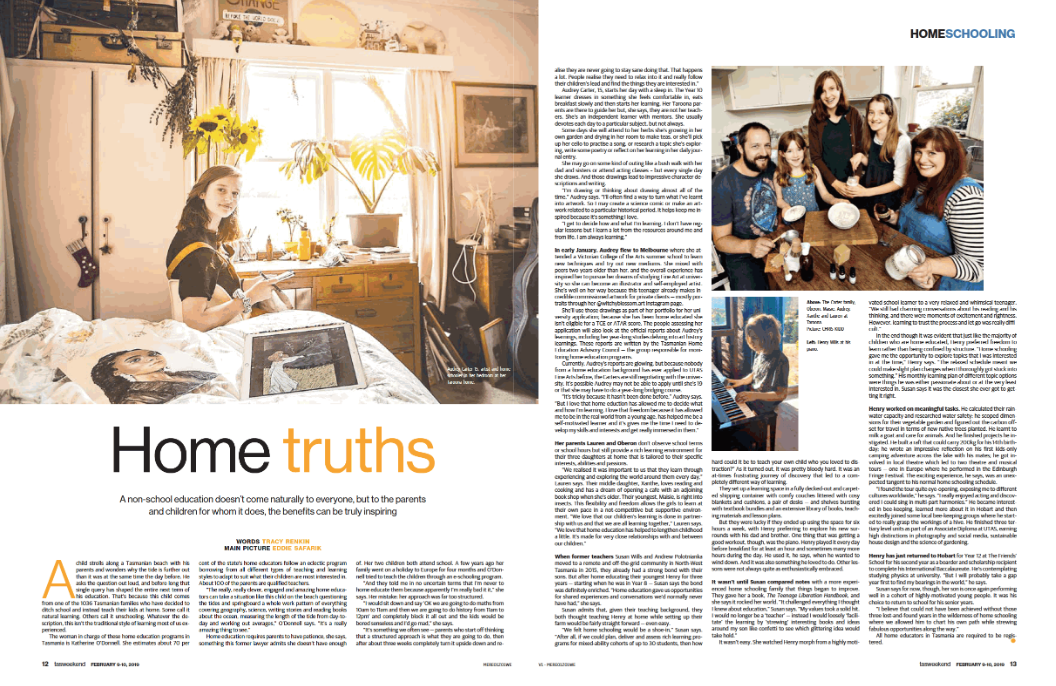

Audrey Carter, 15, starts her day with a sleep in. The Year 10 learner dresses in something she feels comfortable in, eats breakfast slowly and then starts her learning. Her Taroona parents are there to guide her but, she says, they are not her teachers. She’s an independent learner with mentors. She usually devotes each day to a particular subject, but not always. Some days she will attend to her herbs she’s growing in her own garden and drying in her room to make teas, or she’ll pick up her cello to practise a song, or research a topic she’s exploring, write some poetry or reflect on her learning in her daily journal entry. She may go on some kind of outing like a bush walk with her Dad and sisters or attend acting classes - but every single day she draws. And those drawings lead to impressive character descriptions and writing. “I’m drawing or thinking about drawing almost all of the time,” Audrey says. “I’ll often find a way to turn what I’ve learned into artwork. So I may create a science comic or make an artwork related to a particular historical period. It helps keep me inspired because it’s something I love. I get to decide how and what I’m learning. I don’t have regular lessons but I learn a lot from the resources around me and from life. I am always learning.”

In early January Audrey flew to Melbourne where she attended a Victorian College of the Arts summer school to learn new techniques and try out new mediums. She mixed with peers two years older than her and the overall experience has inspired her to pursue her dreams of studying Fine Art at university so she can become an illustrator and self-employed artist. She’s well on her way because this teenager already makes incredible commissioned artwork for private clients - mostly portraits through her @witchyblossom.art Instagram page.

She’ll use those drawings as part of her portfolio for her university application, because she has been home educated she isn’t eligible for a TCE or ATAR score. The people accessing her application will also look at the official reports about Audrey’s learnings including her year-long studies delving into art history learnings. These reports are written by the Tasmanian Home Education Advisory Council - the group responsible for monitoring home education programs. Currently, Audrey’s reports are glowing but because nobody from a home education background has ever applied to UTAS Fine Arts before, the Carter’s are still negotiating with the university. It’s possible Audrey may not be able to apply until she’s 19 or that she may have to do a year-long bridging course. “It’s tricky because it hasn’t been done before,” Audrey says. “But I love that home eduction has allowed me to decide what and how I’m learning. I love that freedom because it has allowed me to be in the real world from a young age, has helped me be a self-motivated learner and it’s gives me the time I need to develop my skills and interests and get really immersed in them.”

Her parents Lauren and Oberon don’t observe school terms or school hours but still provide a rich learning environment for their three daughters at home that is tailored to their specific interests, abilities and passions. “We realised it was important to us that they learn through experiencing and exploring the world around them every day,” Lauren says. Their middle daughter, Xanthe, loves reading and cooking and has a dream of opening a cafe with an adjoining book shop when she’s older. Their youngest, Maisie, is right into insects. This flexibility and freedom allows the girls to learn at their own pace in a not-competitive but supportive environment. “We love that our children’s learning is done in partnership with us and that we are all learning together,” Lauren says. “We love that home education has helped to lengthen childhood a little. It’s made for very close relationships with and between our children.”

When ex-teachers Susan Wills and Andrew Polotnianka moved to a remote and off-the-grid community in North-West Tasmania in 2015 they already had a strong bond with their sons. But after home educating their youngest Henry for three years - starting when he was in Year 8 - Susan says the bond was definitely enriched. “Home education gave us opportunities for shared experiences and conversations we’d normally never have had,” she says.

Susan admits that given their teaching background, they both thought teaching Henry at home while setting up their farm would be fairly straight forward - even easy. “We felt home schooling would be a shoe-in,” Susan says. “After all, if we could plan, deliver and assess rich learning programs for mixed-ability cohorts of up to 30 students, then how hard could it be to teach your own child who you loved to distraction?”

As it turned out, it was pretty bloody hard. It was an at-times frustrating journey of discovery that lead to a completely different way of learning.

They set up a learning space in a fully decked-out and carpeted shipping container with comfy couches littered with cosy blankets and cushions, a pair of desks - and shelves bursting with textbook bundles and an extensive library of books, teaching materials and lesson plans. But they were lucky if they ended up using the space for six hours a week, with Henry preferring to explore his new surrounds with his dad and brother. One thing that was getting a good work out though was the piano. Henry played it every day before breakfast for at least an hour and some times many more hours during the day. He used it, he says, when he wanted to wind down. And it was also something he loved to do. Other lessons were not always quite as enthusiastically embraced.

It wasn’t until Susan compared notes with a more experienced home schooling family that things began to improve. They gave her a book The Teenage Liberation Handbook and she says it rocked her world. “It challenged everything I thought I knew about education,” Susan says. “My values took a solid hit. I would no longer be a ‘teacher’ instead I would loosely ‘facilitate’ the learning by ‘strewing” interesting books and ideas around my son like confetti to see which glittering idea would take hold.” It wasn’t easy. She watched Henry morph from a highly motivated school learner to a very relaxed and whimsical teenager. “We still had charming conversations about his reading and his thinking, and there were moments of excitement and rightness, however learning to trust the process and let go was really difficult.”

In the end though it was evident that just like the majority of children who are home educated, Henry preferred freedom to learn rather than being confined by structure. “Home schooling gave me the opportunity to explore topics that I was interested in at the time,” Henry says. “The relaxed schedule meant we could make slight plan changes when I thoroughly got stuck into something.” His monthly learning plan of different topic options were things he was either passionate about or at the very least interested in. Susan says, it was the closes she ever got to getting it right.

Henry worked on meaningful tasks. He calculated their rainwater capacity and researched water safety, he scoped dimensions for their vegetable garden and figured out the carbon off-set for travel in terms of new native trees planted. He learned to milk a goat and care for animals. And he finished projects he instigated. He built a raft that could carry 200 kilograms for his 14th birthday, he wrote an impressive reflection on his first kids-only camping adventure across the lake with his mates, he got involved in local theatre which lead to two theatre and musical tours - one in Europe where he performed in the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. The exciting experience, he says was an unexpected tangent to his normal home schooling schedule. “I found the tour quite eye-opening, exposing me to different cultures world-wide. I really enjoyed acting and discovered I could sing in multi-part harmonies.” He became interested in bee-keeping, learned more about it in Hobart and then excitedly joined some local bee-keeping groups where he started to really grasp the workings of a hive. He finished three tertiary level units as part of an Associate Diploma at UTAS, earning high distinctions in: photography and social media, sustainable house design and the science of gardening.

Henry has just returned to Hobart for Year 12 at The Friends’ School for his second year as a boarder and scholarship recipient to complete his International Baccalaureate. He’s contemplating studying physics at university. “But I will probably take a gap year first to find my bearings in the world,” he says.

Susan says for now though, her son is once again performing well in a cohort of highly-motivated young people. It was his choice to return to school for his senior years. “I believe that could not have been achieved without those three lost-and-found years in the wilderness of homeschooling where we allowed him to chart his own path while strewing fabulous opportunities along the way.”

All home educators in Tasmania are required to be registered.